International development: let's talk about sex

March 6 2019 - I published this blogpost for International Women's Day in 2019, just after I lost my job at CGD. I tweeted about it, and that is where my story begins.

International women’s day is coming up. It has been marked for over 100 years by protests at the oppression that women around the world face, and celebrations at their hard-won progress towards equality. But in the past few years the question of ‘what is a woman’ has itself become controversial.

In development, ‘gender’ is often used by organisations to mean the issues facing women and girls (and men and boys). It is used as a polite synonym for “sex” and also to encompass the expectations and constraints that societies impose on people because of their sex. However ‘gender’ can also be understood as describing the concept of “gender identity”; the internal sense that some people have of being masculine or feminine, a blend of both, or neither, as well as “gender expression” visible signs such as clothing, makeup and hairstyles (and body modifications) that people can adopt to look stereotypically masculine or feminine. Gender identity and sex are different.

It is increasingly argued across Europe and North America, and within international organisations and foundations that gender identity should overwrite sex as a legal and practical category . Many organisations have adopted the idea that it is personal identity, not anatomy, that determines if someone is a women or a man.

But defining womanhood as a feeling rather than a biological fact has implications for protection of women’s rights. Organisations concerned with social justice, international development and human rights would struggle to articulate their goals, policies and research without a word to denote female people. Yet few are willing to stand up for the biological definition of women, or even to hold open a space for clear, calm discussion. Organisations researching gender and development are coy about saying that by ‘women’ they mean, and have always meant, the female sex. Foundations and international civil society organisations are increasingly calling for governments to allow people to change their legal sex at will, and to access single sex spaces of the opposite sex. But none have promoted analysis or debate about how this would impact women and girls.

It is often assumed that papering over the distinction between sex and gender identity is justified by the principle of inclusion, and that any concerns must be motivated by sexual or religious conservatism; a wish to see patriarchal gender norms upheld, or worse by hatred of transgender people. However increasing numbers of feminist activists, academics, sportswomen (and ordinary individual women and men) are voicing alarm at the rapid mainstreaming of the idea that female people no longer need a name, or specific civil rights protections. They are voicing alarm at the compelled speech being imposed by institutions, and at the rapid expansion in the number of children and young people being given puberty blocking drugs, cross-sex hormones and surgery. While established women’s organisations and human rights groups have largely refused to engage seriously with these concerns, in some countries a grassroots movement has emerged organised by women seeking an opportuity to consider the issue and to speak. For example, in the UK where I live this has emerged via platforms such as Mumsnet, one-women campaigns such as Posie Parker’s Standing for Women, Venice Allan’s We Need to Talk and new organisations such as Fairplay for Women and A Women’s Place (to name but a few of the women who have been brave enough to raise their head above the parapet). Transsexuals such as Miranda Yardley and Debbie Hayton have also spoken out for women’s rights, and about how acceptance and protections for transsexuals is being undermined by the blurring of definitions and aggressive challenges to women’s boundaries. People who raise questions and concerns about the new doctrine that “transwomen are women” have faced censure and silencing; violent protests, no-platforming , job loss and ostracism from their political parties.

Why does the definition of woman matter?

Human rights protections and public policies are needed both for women and girls, and for transgender people, whatever their sex. In order to do this we need to be able to talk clearly and openly.

One argument for changing the definition of women from being about sex to being about gender identity (or gender expression) is one of compassion and inclusion. It is polite to treat people in the way they feel comfortable. People should be free to express their identity. No one should be forced to conform to gender stereotypes or victimised for the way they dress.

However as Professor Rosa Freedman argues ensuring human rights protections for people who are transgender does not depend on accepting the belief that men can become women. The discrimination and abuses that feminine males and transsexuals face are not the same as the discrimination and abuse that women experience “the key is to have specific protections for each group, not to conflate the groups.” (for making statements like this Freedman has received rape threats, and had urine thrown on her office door in the university).

Most of the live policy debates on sex and gender are in North America and Europe, such as over the US Title IX laws on sex discrimination in education, reforms to the UK ‘Gender Recognition Act’ and interpretation protections for single sex services that exist in in the Equality Act. But as Raquel Rosario Sanchez from the Dominican Republic writes the definition of women as a sex is also an issue in developing countries, and debates are being influenced by those going on elsewhere, and by international organisations and donors.

Human beings are a single species, and women and men exist around the world. Amnesty International for example recognise and promote the importance of single sex toilets in refugee camps. Yet at the same time it argues that allowing male people to self-identify into women’s spaces would pose no problem for women and girls in the UK.

Redefining womanhood as an identity based on subjective feeling, or in practice on performance of gender stereotypes, is regressive and undermines our ability to talk about the discrimination, violence and oppression that still affects people because they are born female. There are real, practical harms and risks to women and girls:

- Loss of privacy in single sex spaces such as changing rooms, toilets, dormitories, hospital wards, refuges and prisons if male bodied people are allowed in.

- Loss of dignity if women are forced to accept (without informed consent) to be intimately touched by male people, such as in care for elderly people, intimate searches, airport pat downs, and smear tests.

- Loss of resources and ability to organise in groups and projects set up by and for women (including lesbians), and to understand and organise against sex discrimination, and to overcome barriers that women and girls face.

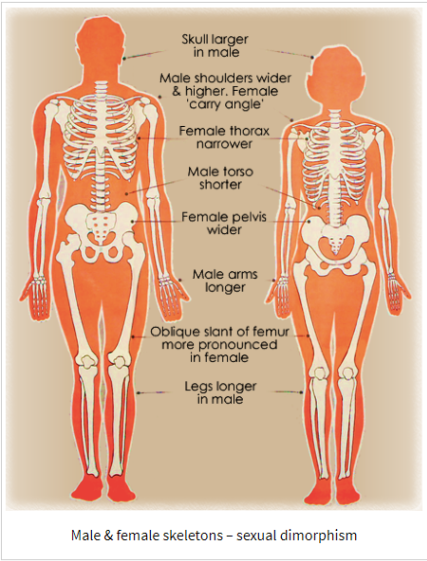

- Loss of female only sports. Males athletes have a 10% advantage of speed and strength over female athletes in most sports. Women and girls will lose sports scholarships and competitive places to people whose bodies are male.

Some in the human rights world argue these are not really harms at all since they believe that there is simply no such thing as ‘male bodies’ and ‘female bodies’. They argue that only bigotry or ignorance can motivate woman and girls to feel uncomfortable changing, showering, sharing sleeping quarters or being searched by a male bodied person, or competing against male bodied people in sport, or for lesbians only to want to date other female people.

However it is likely that most people around the world do not think a person with a male body is a woman. Many women and girls will feel uncomfortable, unsafe and unwelcome if showers and communal changing rooms, hostels, dormitories, women’s refuges and prisons are changed from single sex to ‘single gender’. Sportswomen are increasingly speaking out about the unfairness of opening up women’s sports to male bodied people. The desire to retain female spaces is not based on a belief that all males seeking access are predatory or have any bad motives. But it is clear that some predatory people will exploit a new norm that people who are biologically male have every right to access spaces where women and girls are undressed or vulnerable.

Gender identity in international development and human rights

Thinking about gender identity in international development and human rights organisations is often tied in with sexuality. This reflects the fact that abuse and discrimination relating to transgender identity can be, in practice, an expression of homophobia. Seventy-two states continue to criminalise same-sex sexual activity and homophobic cultural tropes can stereotype gay men as feminine, or as ‘failed men’; reduced to the status of women. In some cultures, men who have sex with men may get some acceptance if they adopt a feminine ‘third gender’ identity such as the hijras in South Asia. But it is worth being clear that there is a conflict between the idea that some people are solely sexually attracted to individuals of the same sex (or the opposite sex) and the idea that biological sex does not matter. This can lead to situations where lesbians face social pressure to have sex with men who identify as women, or where young people who feel same-sex attraction are encouraged to change their gender expression rather than being accepted as homosexual. In Iran homosexuality is punishable by death while sexual reassignment surgery is subsidised and the right to change sex enshrined in law.

It is not at all clear that the way to address the very real problem of discrimination and violence against transgender people is to undermine the fragile and recently established principle of consent; that people should be able to decide if others get to see or touch their body; and particularly that women should be allowed to draw their own boundaries. Feminine and transgender males face abuse in patriarchal societies, not because they are seen as women but because they are seen as an affront to masculinity. Erasing the category of biological sex undermines the ability to define and protect transgender status as a legal characteristic which requires its own protections from harassment and discrimination.

It’s time to talk about sex!

Organisations concerned with international development and global social change seek to support a world where universal human rights are protected and where people can influence the decisions which affect their lives. This should include holding open the space to allow people to talk about the meaning of the word “women”, and about how the rights of both women and transgender people can be protected. People should not have to be brave to talk about this.

Some international NGOs are cautiously beginning to consider these issues and find words to talk about them. Oxfam’s policy on sexual diversity and gender identity for example calls for removal of laws that criminalize or discriminate based on gender identity, while also advocating for women’s rights. They argue that pursuing both these ends demands a context specific approach and close dialogue with local stakeholders. Significantly, Oxfam affirms the right to freedom of thought, opinion, expression and association regarding issues of gender identity and sexual rights.

Here are five principles that may help to hold open a space for dialogue, debate and evidence:

-

Sex and gender identity are not the same. Be clear about what we mean.

-

There should be open and evidence-based discussion on how potential policy changes will affect women’s rights, single-sex spaces, and safeguarding.

-

Women and women’s organisations should be involved in policy debates. The human rights of transgender males should be protected, but it should not be assumed that the best or only way to do this is by undermining women’s privacy, dignity and safety.

-

Data matters. Statistics on crime, employment, pay and health should continue to be categorised by sex. Information on gender identity may also be collected, but they shouldn’t be confused.

-

People who express concern about impacts on women’s rights and women’s spaces should not be dismissed as hateful or bigots

Most of all, while it is polite to refer to people by the name and pronouns they request, and to treat everyone with dignity and respect, inclusion does not demand that we forget about the power dynamics between men and women in society, or fail to notice when women are being told to be quiet and to be kind to protect the feelings, desires and status of male people. Could it be possible that that is what is happening here?